You might have heard you should be ‘reframing’, ‘storytelling’, or ‘shaping the narrative’. But we don’t all want to get psychology degrees, we want to get on with changing the world. This is a Bluffer’s Guide to Framing for busy activists.

I have read and summarised 528 pages of PDFs by framing experts, so you can get on with it – or at least so you can bluff the next time someone lectures you about some TED talk they saw.

[Check out my first Bluffer’s Guide to Framing from 2018]

What are we talking about?

I am definitely guilty of hearing someone use a buzzword one day and thinking to myself: “that’s just a fresh label for what we already tried four years ago”. Then using the same buzzword myself the next day.

So here’s my best try at separating the terms we need to recognise, partly so you can spot when someone else is bluffing.

'Framing'

One of the best definitions I’ve heard is that framing differs from just ‘editing your message to be more persuasive’ because it tries to use science, or at least some kind of testing. It states that our brain needs help simply processing all the info flying at it, so we all have associations and experiences already inside our brain that ‘frame’ anything we see, read, or hear. Therefore it must be possible to experiment with what messages can ‘reframe’ how people see and react to your issue.

The classic example is when researchers showed members of the public two identical articles about an urban crime wave: when crime was described as a ‘beast’ it provoked more support for police enforcement, but when the metaphor was changed to ‘virus’ readers were more sympathetic to social reform.

'Storytelling'

The inspiration for storytelling structure is usually Joseph Campbell’s “The Hero With A Thousand Faces” from 1949 and his theory that in all types of stories, all around the world, a recurring 12-step ‘monomyth’ creates a compelling “Hero’s Journey”.

Especially since Jonah Sachs’ “Winning the Story Wars” was published in 2012, campaigners and advertisers alike have been encouraged to use storytelling structure as a vehicle for their non-fiction communications too. Even more than framing, this communications trend has exploded in the past decade with everyone from mattress brands to life coaches to the Game of Thrones finale going on about the persuasive power of storytelling.

That might be too cynical – good storytelling is crucial, but we’re still lacking much robust evidence it has uniquely magical powers (as Daniel Stanley argued in Stir to Action magazine) and there is even a warning from the Topos Partnership that

“close-up portraits of individuals are a type of story that, when treated as a main focus of communications, almost always works against building support for progressive policy change”.

'Narrative'

I’ve generally found that ‘shaping the narrative’ gets used as a euphemism to signal that someone is ‘thinking bigger’. Specifically, what they mean by narrative is a larger worldview that is influenced by stories and framing, and what they’re trying to do is something more holistic and long-term that draws from both storytelling, framing, as well as other evidence.

You’ll now sometimes see this also described as ‘strategic communications’, which is – confusingly – not describing communications which are strategic, but is more like a general label for this interdisciplinary, overarching practice.

Pretty much every influential thinker on these subjects in the USA spoke to the Narrative Initiative for their ‘Toward New Gravity’ report where their analogy was:

“What tiles are to mosaics, stories are to narratives. The relationship is symbiotic; stories bring narratives to life by making them relatable and accessible, while narratives infuse stories with deeper meaning.”

'Cognitive Linguistics'

A combination of linguistics and psychology that is concerned with how language can change how we think, and how the way we think changes language. This is the academic discipline that gave framing its evidence base, beginning in the 1980s but becoming popular amongst progressives with the 2004 book “Don’t Think of An Elephant” (more in the previous blog’s short history of framing).

This could sound quite similar to ‘social priming’, the study of how tiny, subtle cues can have dramatic subconscious effects on our behaviour, but for some reason that field in particular seems to have become the punching bag of the psychology field.

Confused? Me too, so my approach is to pay attention to the science, but not get too devoted to a single study, field, or scientist, because they seem to all be flailing about just as much as the rest of us.

Do definitions matter?

Most people will probably use these terms pretty much interchangeably with no problems, but I think there’s value in trying to draw relatively tight lines around terms if we are going to use them.

The broader the definition the less meaningful it is, and the more laziness in application, as warned by Brett Davidson of Open Society Foundations:

“Hardly a conversation or meeting happens without the term ‘narrative change’ being used. However there is always a danger when a term becomes a trend, because it starts to become a short-cut for thinking – a term without precision – where everybody thinks they know what it means, but nobody really does for sure.”

Why be careful?

What would my inner sceptic say? For a start, there might be some advertising pioneers or Greek philosophers who are smirking from beyond the grave that – just like each generation thinks they have invented sex – each era thinks that they have invented the concept of playing with wording to persuade people.

Research reports very rarely get into the nitty gritty of how you apply insights when you get into the office on Monday morning, so here are some common traps I’ve seen fellow campaigners fall into. Do you recognise any of these?

“I just feel it’s better framing”

People using the buzzword as cover for their personal taste in copywriting or personal policy preferences about what the content of the message should be.

“Have we followed the model in these comms?”

Storytelling structures and framing models are great when they provide prompts to get started. Not so great when they turn into rigid templates which leave junior communications staff struggling to fit all 12 steps of the hero’s journey into a tweet.

“People will get turned off if you put those facts in”

Plenty of evidence has emerged that bludgeoning audiences with statistics can actually turn them against you – but that has seemed to lead to a lazy overcorrection against the use of facts. The problem with over-learning from the wilful anti-empiricism of reactionaries is that us progressives need people to value expertise and evidence.

What is actually helpful?

My day-job is to take these insights and theories and try to turn them into words, pictures, or activities that are simple for organisations and activists to use in their day-to-day campaigning. Because we are all acting under more financial, time, and legal constraints than ever.

So this is what I’m looking out for in this Bluffer’s Guide to Framing:

Choice:

Is it just reheating truisms like “be positive rather than negative” and giving us a long list of values we need to tick off? Or is it giving us Do’s and Don’ts that are meaningful because they actually address mistakes that we might make and redirect us to choices we might not have thought of otherwise?

Evidence:

Is there some attempt at providing evidence for a particular recommendation? An alarming number of justifications seem to solely cite social media reach of a video, the simple existence of Trump/Brexit, a ‘focus group’ that is actually just a roundtable of NGO staff, or just assert “studies have shown”.

Quality:

Communications is a craft, and if a framing project’s output is ugly, meandering and poorly written it undermines the conclusions. Is there some nugget of imagery or phrasing that we might conceivably use in our day job, some spark of creativity that lifts the quality of our work?

Tools:

Is the only way of communicating the insights to sit someone through a 20-slide powerpoint? Or has the project tried to promote itself to a wider audience, and provided us with useful tools to make it easy for us to implement those insights and share them with others?

I’m kicking off with ‘race-class’ as a must-bluff in 2020.

Not just because I’m summarising a couple of projects on migration and poverty, but because the ‘Race-Class’ Narrative is typical of the way that the conversation around framing has changed the past few years: more explicit collaboration between social movements and electoral politics; more proper testing and promotion; a rejection of simplification and pivoting; and an appreciation that no proper progressive campaign can simply ignore the ‘culture wars’ but has to take it on.

"Race-Class Narrative"

Anat Shenker-Osorio, Ian Hany-López & Demos

“We cannot meet people where they are because where they are is unacceptable. The job of a good message is to make popular what we need said.”

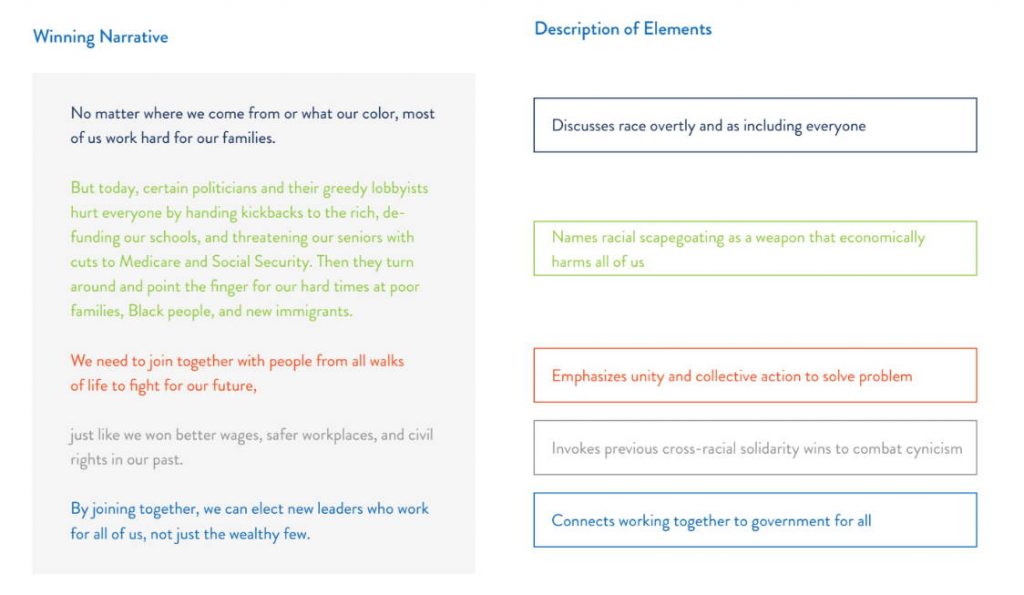

This ongoing project is probably the most influential framing experiment of the past two years. It attempts to answer a continual dilemma for the Democratic Party in the USA, which is relevant to us all: how do you react to conservatives using racism to ‘divide and conquer’ the middle and working classes?

Unfortunately the original research report is incredibly dense, so it is well worth your time to read this Salon article which is the best written explanation I’ve seen. But I’ll give you my bluffer’s summary:

• The threat: The US Right has stoked voters’ racial fears and resentments, undermining solidarity between working people for the progressive policies which would benefit them all.

• The response: Conventional wisdom has been: “Don’t take the bait – if you respond to racism you only continue a losing conversation, focus on economic issues instead”.

• The dilemma: Simply trying to change the subject is not working – the conversation is still happening in voters heads but now they can only hear the racist voices.

• Hypothesis: We have to explicitly confront the racist argument by telling voters it is a deliberate tactic to divide them, and that the motivation behind this divisive tactic was to benefit the rich at the expense of everyone else.

• The results: They tested different adverts and found the best responses exposed this “causal connection” between racism and elite greed, and contrasted that division with a message of ‘unity’ instead. This was not just motivating for the ‘base’ that already agrees with progressive views but was also more sucessful than other approaches with ‘persuadables’ in the middle.

You really should read that article – the actual execution of the adverts is fascinating – but here are some more of my favourite things about this project, and its continued influence.

People are contradictions

“Because the persuadables are completely and totally capable of having progressive views on race, among other things, but also completely and totally capable of believing bullshit, when we are silent about race … we simply allow the other side to be the only message received.”

Race-Class? Not Race/Class,

or Race&Class?

“That is why I bring you a race-class narrative. … It is not a “race & class narrative.” It is a narrative that weaves together race and class and makes a causal connection between these two issues. It explicitly names the need for cross-racial solidarity in terms of joining together with people of other races, joining together across racial difference. Not some generic, Kumbaya, we-all-need-to-get-on-the-same-page, we-all-need-to-get-together, we-all-need-to-be-as-one. It actually names racial difference.”

Promotion

There have been other projects along similar lines, and the cynical view I’ve heard of why Shenker-Osorio has dominated conversation is ‘she just markets herself better’.

But I think that is one of the best things about it! So many great framing insights die a death after a single PDF and a couple of conference keynote speeches.

In contrast, Shenker-Osorio has been on what feels like a three year promotional tour:

• Multiple speaking events in the US, Europe and Australia.

• Appearances in the Washington Post, the Guardian, and the cult-hit podcast Pod Save America.

• Launching her own podcast (‘Brave New Words’) which dives into a case study of great framing in campaigns each episode.

• As politicians start actually using this insight more, Shenker-Osorio remains willing to get into the fray on Twitter with day-to-day examples of bad or better framing.

And most excitingly, Demos have combined this research with some of the best minds in storytelling, and leading groups in the progressive movement, for a project called: ‘Our Story: A Populist Meta-Narrative for Our Moment’

"Talking About Poverty"

Joseph Rowntree Foundation & FrameWorks Institute

“The economy we have today was designed, and it can be redesigned to work for everyone.”

For this project the Joseph Rowntree Foundation teamed up with Frameworks Institute, a US outfit specialising in framing that has increasingly worked in the UK too. They aimed to “change the story we tell about poverty…. so we can call more loudly for the solutions.”

The full report is here – and these are my favourite bits:

Know your elephants

A warning of specific frames that can easily be unintentionally triggered by campaigners, but which could block support for tackling poverty:

“Post-poverty”

people don’t believe poverty exists today, in this country.

“Self-makingness”

people blame individuals for being in poverty, and believe they should try harder and work more. They don’t see the wider context.

“The game is rigged”

people think there will always be

poverty and nothing will ever change.

I find it really interesting that the UK-based PIRC (Public Interest Research Centre)’s ‘Framing the Economy’ report in 2018 found very similar results to this question.

Choices

Building on the identification of specific frames to avoid triggering, the report also suggests a table of Do’s and Don’ts.

I would have liked more examples of how to do it when you are delivering real-life comms with real-life tradeoffs, but some of the Don’ts are really useful as they highlight rhetorical habits that it can be easy to slip into.

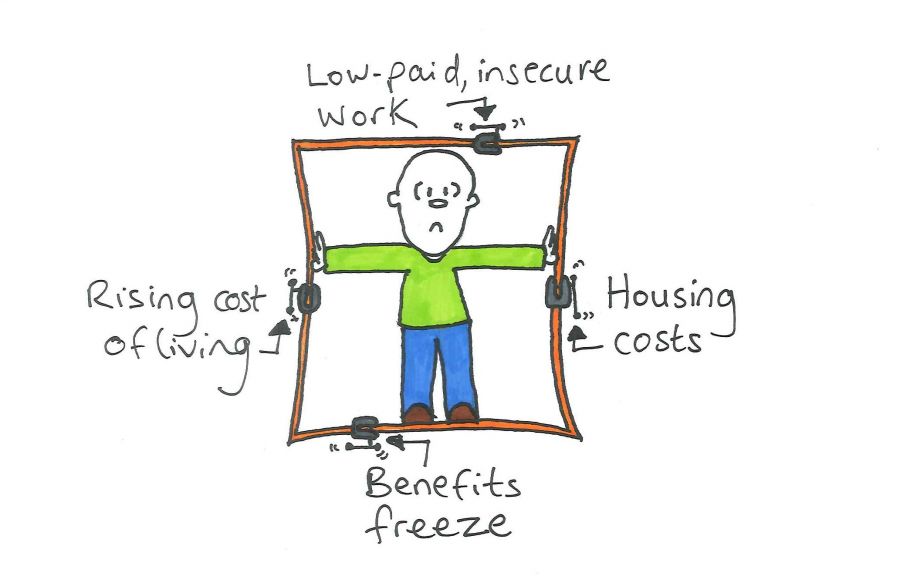

Visual metaphors

The report comes with a series of doodles to experiment with reframing poverty visually.

My favourite is ‘the economy locks people into poverty’. This tackles the problem of no single factor being the sole cause of poverty (“Well my rent has also shot up, but I don’t count as ‘poor’, why can’t they deal with it?”).

By portraying poverty as a tightening vice of various pressures, it both shows the shrinking breathing space to be able to plan your way out of poverty, as well as the constant threat that one small change could collapse your world entirely.

"Crafting an evidence-based narrative around migration"

British Futures & Apolitical

In May a conversation on “best practices necessary to frame narratives around migraiton in a healthier, more evidence-focused direction” was hosted on Apolitical, a learning platform for civil servants.

At the workshop and in an accompanying article Sunder Katwala of the think-tank British Future laid out lessons that draw from British Future’s 2014 report ‘How to talk about immigration‘.

Know your elephants

The article dissects the populist story of migration:

“There are too many of them”

a story about numbers.

“They are taking our stuff”

a story about resources.

“They are not like us — and they don’t want to be”

a story about identity.

“We aren’t even allowed to talk about it — or they call us racist”

a frustration about voice and democracy.

Tools to help the day job

How often do you bookmark an interesting webinar and not turn up, or turn up and vainly try to multitask? Apolitical wisely acknowledge this with a good follow-up page that includes the recording, resources, and even a link to an online skills course to boost civil servants’ confidence to actually use this framing advice.

Choices

Sunder’s article ends with five tips on how to talk about migration – I think his last two are the most useful:

Get beyond “they are good for us” – tell stories of the “new us” instead

Tell ordinary stories, not just extraordinary ones.

"Communicating Global Justice & Solidarity"

Framing Matters for Health Poverty Action

The international development sector has not been happy with the term ‘international development’ for years, but along with the terms ‘charity’ and ‘overseas aid’, it has been unable to discard the vocabulary because it is still busy defending the principles.

Along with members of the Progressive Development Forum, Health Poverty Action aimed to “create a new narrative – one that builds solidarity and demands social justice.”

As well as the step-by-step tips that have been honed by PIRC over the years, author Ralph Underhill adds the personal touch of ‘animal traps’ as a cute way of distinguishing between the specific framing pitfalls to avoid.

Read the full report here.

Parrots

Refutation trap!

Don’t just repeat what they say.

Sharks

Contaminated language trap!

Negative assocations.

Chameleons

Sanitising/obscuring trap!

Hiding in plain sight.

Robins

Rose tinted trap!

Positive associations that might not help.

If 2019 does end up being the turning point in the world’s efforts to tackle the climate emergency, then “Our House is on Fire” and “Tell the Truth” will deservedly join “I Have a Dream” in the history of rallying cries. However, arguably the impact of the School Strike for Climate and Extinction Rebellion has had less to do with particularly original framing, and more to do with the other factors in making large-scale change: such as strategic direct action, compelling messengers and distributed organising structures.

This also shows the value of people who are unencumbered by the sector’s research and just get out there and test messages through action. There is no better proving ground for a messaging slogan than whether it becomes a popular placard.

Below I’ve summarised some insights on telling the truth on climate change and other issues: from some new thinkers, one institution that has existed for a couple of centuries, and some cultures from even longer ago.

Newspapers not neutral on nature

Media outlets made two major breakthroughs in 2019. One was belatedly realising that most of the public only ever see the social media preview of an article, so they better be careful with headlines and headline images. The other was appreciating that there is no such thing as totally impartial, journalistic neutral language, and so being more proactive in using language that improves the public’s understanding.

The Guardian was one of the first to do this through a change in their style guide on climate change, and many others have followed, or are taking it to other areas such as The Correspondent’s ‘Glossary of Othering Words‘

+BREAKING+

— Leo Hickman (@LeoHickman) May 17, 2019

The Guardian's editor has just issued this new guidance to all staff on language to use when writing about climate change and the environment... pic.twitter.com/yylPXJzdbc

Here are my suggestions on how to talk about the living world with words that engage people, reveal rather than disguise realities, and honour what we seek to protect. pic.twitter.com/FdrMNJGO0B

— George Monbiot (@GeorgeMonbiot) November 1, 2018

Green New Deal: recognition vs resonance vs relevance

As popularised by US Congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, the Green New Deal has been praised for its framing of environmental action as something which will provide domestic jobs and economic stimulation, in a callback to President FDR’s New Deal in the 1930s.

Movements in the Global South have led this use of ‘progressive patriotic nostalgia’. The concept of swaraj is associated with Gandhi and ‘self-rule’, and so Indian environmentalists have been describing radical ecological democracy as ‘eco-swaraj’. The ancient Latin American and Indigenous concepts of ‘buen vivir’ and ‘sumak kawsay’ – which are about communal and regenerative balance with nature – have been rediscovered as 21st Century ways to reframe what a ‘good life’ means.

In the UK there has been a debate within progressive circles whether to piggyback on the popularity of the Green New Deal, to broaden it out to a ‘Global Green New Deal’, or to tailor it to British history as a ‘Green Industrial Revolution’. This is a classic framing dilemma of balancing existing recognition vs research-tested resonance vs policy relevance. The fact that the opposition Labour Party has switched back and forth three times suggests this debate is not settled yet.

Note: To further complicate things, the concept of the Green New Deal was actually invented by UK campaigners in 2007, and ‘Green Industrial Revolution’ was coined by Tony Blair in 2001. It just goes to prove that ‘coming up with the phrase’ is just one part of the framing puzzle.

We need a #GreenIndustrialRevolution to tackle climate change and transform towns across the UK that have been held back for decades.

— Rebecca Long-Bailey (@RLong_Bailey) May 13, 2019

But that won't happen by itself.

It'll take all of us, working together. So get involved with @UKLabour and let's take our future back. pic.twitter.com/OQhd9LyvRW

"The Power of How: An Explanation Declaration"

2019 was the Frameworks Institute’s 20th anniversary. They’ve been giving their perspective on trends in framing over that time, making the case for explanation as a vital tool that is being lost through “critical flaws in narrative practice”. Two highlights for me:

• It gives a great distinction between definition (the borders of what something is and isn’t), description (a list of its characteristics) and explanation (an invitation to understand how something works)

• It takes ‘Thinking, Fast and Slow’ (a book I bought just like everyone else but struggled to make past chapter 3) and applies the insights of ‘System 1 and System 2’ thinking to the case for why we should not skimp on explanation – or ‘fast’ thinking will explain social change as the problem of individual choices rather than structural causes.

Read the short and well-written brief here.

There’s so many resources on framing and narrative coming out at the moment. There’s also lots of people using the buzzwords very liberally! Both trends should encourage you to feel like good framing is not something that you have to ‘leave to the experts’. If you’re thinking about choice, evidence, quality and tools to help others implement your findings, everyone serious about progressive change – whether you are in politics, NGOs or activist groups – can get a lot of value out of doing their own framing work.

These are some great recent tools to do that.

"Be The Narrative"

JustLabs and the Fund for Global Human Rights

Probably my favourite single framing document of the past year, this project is a collaboration between Krizna Gomez of JustLabs (a social change collective with roots in Colombia) and Thomas Coombes (former Head of Brand at Amnesty International who made big waves by shifting framing internally).

It ticks most of my boxes:

• Well-written definitions of framing compared to narrative.

• Links what NGOs need to say differently with what they need to do differently to avoid hypocrisy and ‘build narrative muscle’.

• Actually tries to creatively execute its insights with groups in different countries trying out campaign prototypes.

• Beautiful illustration! If you are asking someone to read a 50-page PDF, please help our eyes out.

Read the full report here.

"A Larger Us"

The Collective Psychology Project

Alex Evans, a former government advisor and Avaaz campaigns director, has been writing for years about the need for framing “a larger Us, a longer Future, a different Good Life.” Reflecting the increased appetite of foundations to fund this kind of work without NGOs, he now heads up the Collective Psychology Project, which launched in late 2018.

Two things it has added to my thinking:

• If people are going to play with pseudo-science when we talk about framing, we might as well just call it psychology and use real psychological insights.

• Rather than trying to each come up with our own Universal Original Model™, why not collaborate on things like CPP’s framework for what needs we have (internal as well as relational) and map the existing methods and leading examples out there, so we can tap into the work that everyone is already doing?

Their first report – ‘A Larger Us’ – is here.

Feminist Realities Toolkit

AWID (Association for Women's Rights in Development)

“We believe that Feminist Realities are not only possible but that they exist now, in the many small and big ways people and movements live, struggle and build. We understand Feminist Realities both as current, existing practices that people and groups are forging as well as the ideas, ways of thinking and doing, the proposals that are in the works. These Feminist Realities go beyond resisting oppressive systems to show us a what a world without domination, exploitation and supremacy looks like. Feminist Realities are our power in action.”

AWID have created this toolkit as part of their multi-year strategy as a truly global (and largely Global South) membership organisation supporting the wider feminist movement.

Strictly speaking, this toolkit focuses more on storygathering and storysharing, but its really useful for anyone interested in framing by doing, because:

• It has a clear theory that the feminist movement needs to not only respond to threats but make bold propositions about the better world that is possible – and that they can do that through ‘storytelling as resistance’.

• It features the voices of people outside the usual NGO/activist hot spots, such as sex worker movements in Mexico and transgender groups in Pakistan.

• It mostly consists of step-by-step guides to doing public speaking or facilitating workshops, from quick practices on the street, to 2 hour or even 2 day sessions.

• It is beautifully designed with illustrations and photographs that show the kinds of feminist realities it wants instead of just talking about them.

The full toolkit is here:

Framing to follow in 2020

Expect to see interesting things coming from a group of climate activists who are nearing the end of a year-long ‘Framing Climate Justice Project’ run by PIRC, 350.org and NEON.

Friends of the Earth Europe worked with PIRC to find a narrative for ‘The Europe We Want’ that started in the 2019 European Elections.

The big discussion within the international development sector under the tagline #ShiftThePower has dived into the ‘globaldev’ narrative in a series of webinars – summarised here.

If you’re interested in the work of the Collective Psychology Project, the think tank More in Common is generating a lot of research on behaviour, media and communications around polarisation in the US, UK, France & Germany.

The US-based membership body Communications Network is holding an event in Denver on 19th February with Trabian Shorters, who has been advancing the case for ‘asset framing over deficit framing’.

The UK-based membership body Charity Comms is holding an event in London on 5th March: Changing Hearts and Minds: Social Science Insights for Communicators

The Mobilisation Lab twice-monthly newsletter is still the best place to find out about campaign methods and successes across the world.

Blueprints for Change – a volunteer-run library of Google Docs How-To guides to the latest campaigning techniques – has had requests for more guides, why not join them?

I’ve tried to include more examples from outside of UK & USA this time but it’s still obviously mostly English-language. There are some great initiatives happening here in the Netherlands which demonstrate how universal some of the questions are, but how culturally-specific some of the answers may need to be:

• The Tropenmuseum in Amsterdam – reckoning with its legacy as ‘The Colonial Museum’ – has created ‘Words Matter: An Unfinished Guide to Word Choices in the Cultural Sector’ (English version here)

• Partos, the Dutch membership body for international development NGOs, has started their own research project into framing in the Netherlands.

…and finally, campaigner discussion in 2020 will be dominated by the US primary and general elections. So whoever wins, expect to see blog posts heralding their framing popping up all over the place.

Wanna sign up to my emails?

I send them 2-3 times a year with personal stuff about integrating in the Netherlands, work stuff about the activists I support, and resources I find or create – like this guide!